I regard the ‘ability to perceive, understand, imagine, communicate and act’ as the fundamental starting point for any theory of the mind. You will find this discussed in the first chapter of my book ‘Rethinking the Mind’. This post concentrates on perception (the first of the five abilities) and what it is.

Representationalism

The predominant idea in modern neuroscience concerning perception is that what we perceive are images or representations in the brain. In other words the world around us is an hallucination created by the brain. (See for example [Seth2017] ).

This view is known as ‘Representationalism’.

It is wrong.

What we perceive are the various objects, and their attributes and behaviours in the real world.

‘Hallucination’ in common parlance means ‘seeing or hearing things that are not there’. According to psychology professor Benny Shanon of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, [Shanon 2003] the characteristics of those things we describe as hallucinations are:

- “Vividness: subjectively the experience is that of a vivid perception.

- Non-correspondence: Factually the experience does not correspond to any real objects or state of affairs in the real world.

- Ignorance: the cognitive agent however is not cognizant of 2).

- False Judgment: hence the hallucinatory experience involves false judgment on the part of the cognitive agent.

- Negative evaluation: Thus overall the hallucinatory experience is evaluated pejoratively, and it is assumed that it is of no positive import. Typically experience is taken to be indicative of some psychological impairment.

- Dismissal: Implied in all this is the assessment that any person other than the one having the hallucinatory experience will adhere to the negative evaluation indicated in 5).”

So to classify perception as an hallucination is to deny all objective criteria about what is and what is not. This justifies the current philosophical fad called ‘postmodernism’.

Postmodernism is a term applied to certain approaches in the social sciences and philosophy. It is characterised by ethical relativism and subjectivity. It emphasises the social construction of ‘knowledge’. It is generally sceptical towards science. Thus, “if it’s true for you, it’s true”; “there are facts and alternative facts.”; “there is western truth and Russian truth” etc.

Perhaps rather than neuroscience validating postmodernism, it is the other way around. Perhaps ‘neuroscience’ as it is currently practised is on rather shaky philosophical ground.

Direct Realism

The Scottish Enlightenment philosopher Thomas Reid (1710-1796) long ago recognised that we cannot deny certain principles consistently. Among these principles is: “Those things that we clearly perceive by our senses really exist and really are what we perceive them to be.”[Reid 1785]

For if we deny this principle we cannot meaningfully converse with others. You might think this thing is a lion but I think it’s a typewriter.

Reid’s principle is known as ‘direct realism’.

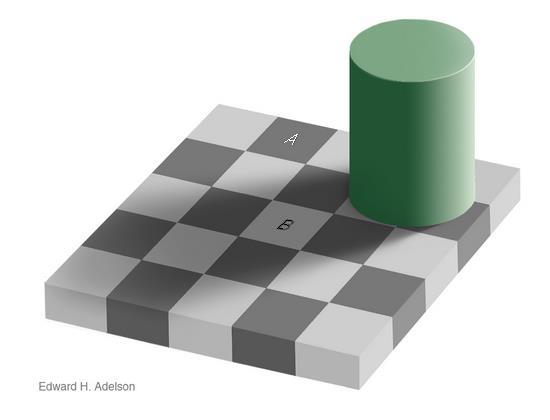

Reid did not deny that our senses can deceive us. Neuroscientists are forever finding new ways in which they can. In the picture above the two areas labelled ‘A’ and ‘B’ appear to be different shades of grey (Adelson’s chequerboard illusion). They are actually the same which is obvious when we block out the rest of the picture as here:

Reid did not deny that our senses can deceive us. Neuroscientists are forever finding new ways in which they can. In the picture above the two areas labelled ‘A’ and ‘B’ appear to be different shades of grey (Adelson’s chequerboard illusion). They are actually the same which is obvious when we block out the rest of the picture as here:

But it does not follow that because our senses can be deceived that they always are. Or even that they are deceived most of the time. We can be caught up in a movie and identify with the characters, but we can still recognise the fact that it is a movie.

Once the chequerboard illusion above is pointed out, we recognise the truth. Only postmodernists and neuroscientists conclude from that that nothing is real.

Neuroscientists could retort that because everything goes on in the brain neuroscience knows that the brain is real. They profess to be good card-carrying materialists. This is an inherent contradiction with the idea that the world is an hallucination.

You perceive by using your senses of sight, hearing, taste and smell. You see with your eyes. You hear with your ears etc. You do not see, hear, taste or smell with your brain. The brain is not an organ of perception, even though you cannot see, hear etc without the brain. You, the person, is what perceives, and this is manifest in the way you act and communicate.

The senses are not infallible. It is possible to find that what you thought you perceived was not actually what was there. In this case you say, “I thought … but it turned out that …”.

JJ Gibson

The psychologist JJ Gibson (1904 – 1979) classified vision in four distinct levels [Gibson 1986]:

- Snapshot when the eye is stationary and functioning like a camera;

- Aperture when the eye is able to scan the environment from a fixed position;

- Ambient when the organism is able to turn its head and look around;

- Ambulatory when the organism can walk around.

Gibson investigated these types of vision. In one experiment he had subjects look through a camera shutter so that they obtained a ‘snapshot’ wide-angle view of the environment for a fifth of a second. The subject had to find out what objects were on a table in front of him. He could take as many ‘snapshots’ as he liked and he could scan the table by moving his head.

“Perception was seriously disturbed and the task was extremely difficult. What took only a few seconds with normal looking required many fixations…there were many errors.”

Gibson emphasised the need for a person to move and see things from different perspectives to perceive what is really there. There are several clues in the environment during ambulatory vision such as perspective, parallax, occlusion of one surface by another and so on that locate an organism in its environment. In particular the organism can perceive itself as well as its environment. “Information about the self accompanies information about the environment” because we perceive parts of our own bodies.

Gibson’s experiments reveal that perception is not a passive process whereby photons strike the retina and stimulate various neural processes which are labelled as ‘perception’. It is an active process where the person deliberately changes his viewpoint (by moving his eyes, head and body) to extract from the environment those things that are invariant. Thus we perceive a table top as a rectangular surface even though all the retinal images relating to the table top are trapezoids of varying shape.

Perception does not produce ‘mental representations’. Perception enables the organism to function in its environment through active exploration.

So perception is the process whereby we get knowledge of our environment and the objects in it, their attributes and behaviour, and events.

References

[Gibson 1986] Gibson JJ (1986) The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

[Reid 1785] Reid T Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man Essay 6 Chapter 5 p253-263 avaialable at http://www.earlymoderntexts.com

[Seth 2017] Seth A Your brain hallucinates your conscious reality TED Talk 18 Jul 2017 available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lyu7v7nWzfo

[Shanon 2003] Shanon B “Hallucinations” Journal of Consciousness Studies vol 10 (2) p3