by Michael Davidson

Thomas More

Thomas More (1478-1535), Lord Chancellor to Henry VIII (1491–1547) of England, wrote the book ‘Utopia’[1] first published in 1516. The book describes a fictional island and its politics and customs. The word is derived from the Greek ou = not and topos = place, hence utopia = no place. There is also the Greek eu = good which sounds similar, so utopia = good place (the current meaning). It is not clear whether More was presenting this mythical island as the perfect state or whether he was saying no such place could stably exist. Given the political climate of the time he was probably wise to be equivocal on the matter. He eventually lost his head anyway.

There is no private property or money on Utopia. All produced goods are stored in warehouses where people get what they need. All property is communal so houses are periodically rotated between citizens. All meals are communal. There are no private gatherings. All wear similar woollen garments. Premarital sex is punished by enforced lifetime celibacy. Adultery and travel within the island without a passport are both liable to be punished by enslavement.

You might not think that this would be a pleasant place to live, but there has been at least one attempt to implement such a society (Michoacán, Mexico circa 1535) and More was revered by Lenin for promoting the “liberation of humankind from oppression, arbitrariness, and exploitation.” [2]

Plato

Thomas More mentions Plato (427-347BC) favourably, and was obviously well acquainted with Plato’s Republic [3] which is arguably the first attempt to design a ‘perfect state’. In Plato’s republic there are 3 classes of citizen: the rulers, the military and the workers (merchants, carpenters, cobblers, farmers and labourers). The rulers are the philosophers (those devoted to reason); the military (called Guardians) are the spirited or ambitious; and the rest are those who know only their desires. The rulers rule with absolute power, exercise strict censorship so that only good and true ideas prevail, and ensure by appropriate education that they are succeeded by like minded philosophers. All citizens know their place in society and may not change it, for to do so would be to rebel against the institutions.

For the rulers and the potential rulers, family life would be abolished in favour of communal living. All promising children who showed spirit or reason (from whatever class – though Plato advocated a eugenic program of mating the ‘best men’ with the ‘best women’) were to be removed from their families to be educated as potential rulers. Their training would be in gymnastics and military music until the age of twenty. Then mathematics and astronomy for ten years, followed by a thorough study of Plato’s philosophy. Those that didn’t quite make it through the course at any stage were to be assigned to the military. By the time they have successfully finished this study they will be over 50, will have developed such a devotion to Plato’s philosophy that they will rule only through their sense of justice which requires their ruling wisely in recompense for the superb education the state has provided for them. Since the rulers are just, good etc and they have absolute powers there is no need for laws or votes.

Thomas Hobbes

More and Plato were idealists who believed in worlds beyond this one. But totalitarian states can also be based on a materialist view of Man. Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) in his book Leviathan (1651) regards the State as something like an artificial man “the sovereign is the soul, the magistrates are artificial joints, reward and punishment are the nerves, wealth and riches are the strength” and so on.

Hobbes thinks that ‘in the state of nature’ Man is or would be in a perpetual state of turmoil. Without “a common power to keep them all in awe”, there would be a war of “every man against every man.”[4] The solution is for men to surrender their liberty to a sovereign power. It does not much matter whether the sovereign power is a monarchy, an aristocracy or a democracy. The essential point according to Hobbes is that the sovereign must have absolute power. Only in this way can the populace have a secure and orderly existence.

Such perfect societies would not be so bad if they were confined to books, but every so often societies built on similar lines spring into being. This is often the result of a revolution or coup in the name of some dream. Whereas these societies tend not to last long, reversing the process to a more libertarian one is often painful. It is not usually possible to impose democracy on what was previously a dictatorship. Although democracies may be born in a coup they also evolve, as is evident in the many different versions of democracy that exist in the world today.

John Locke

Freedom of speech, freedom of enterprise, rule of law, property rights and the ability to remove unpopular governments from power without disrupting society are characteristics of democracies. In popular parlance only voting is seen as distinguishing democracy from other systems. But there is a lot more to it than that.

The above characteristics are attributed in no small part to John Locke (1632–1704) who published Two Treatises of Government in 1689 [5] which seeks to throw light on the basis of political authority. Locke does not reckon much to Hobbes’ absolute sovereign power. He sees the original ‘state of nature’ as happy and tolerant. The State is formed by a social contract which entails a respect for natural rights, liberty of the individual, constitutional law, religious tolerance and general democratic principles. The various institutions form a system of checks and balances. A government must be deposed if it violates natural rights or constitutional law. The state is concerned with procuring, preserving, and advancing the civil interests of the people: life, liberty, health and property through the impartial execution of equal laws. These principles were eventually enshrined in the constitutions of many modern democracies as ‘self evident’. The history of the world shows there was nothing much about them that was evident before Locke. The whole idea of ‘human rights’ (ie those rights arising from being a human being as opposed to sovereign rights, marital rights etc) stems from this era and can be attributed to Locke in no small part.

Montesquieu

Democracies depend for their equilibrium on many interdependent and independent institutions. The doctrine of the ‘Separation of Powers’ due to Montesquieu (1689–1755) was based at least partly on his observation of Locke’s England. This had recently become a constitutional monarchy through the “Glorious Revolution”(1688) which installed William of Orange and his wife Mary on the throne with increased parliamentary authority. According to Montesquieu political liberty is a “tranquillity of mind arising from the opinion each person has of his safety.” In England this was obtained through the separation of the Legislative, Executive and Judicial branches of the administration.[6] The merging of these powers into one body would be a recipe for tyranny, he said. The separation of powers was a major consideration in the drafting of the US Constitution (1788).

According to Montesquieu democracy can be corrupted not only where the principle of equality of all citizens does not exist but also where the citizens fall into a spirit of ‘extreme equality’ where each considers himself on the same level as those who are in charge. People then want to “debate for the senate, to execute for the magistrate, and to decide for the judges. When this is the case virtue can no longer subsist in the republic.”[6] The ideal of a ‘Free Press’ exists so that corruption in high places can be exposed, but it can deteriorate into this ‘extreme equality’. This is shown by the recent scandals in England where certain sections of the press have represented themselves as the conscience of the nation in all matters political and judicial whilst at the same time having so little respect for the truth in high profile cases like Christopher Jefferies¹ and engaging in criminal activity like phone hacking².

¹Christopher Jefferies was a retired school teacher and the landlord of Joanna Yates who was murdered in 2010. Jefferies was arrested but released without charge. The press hounded Jefferies who eventually won substantial damages for defamation of character by several newspapers, and two newspapers were found guilty of contempt of court for reporting information that could prejudice a trial. Another man was later found guilty of her murder.

²The private voice mails of the Royal family, politicians and celebrities were hacked into by journalists of The Sun, The News of the World and The Daily Mirror for the sake of a story. This became the subject of the ‘Leveson Inquiry’ in 2011. [7]

Thomas Paine

One of the foremost polemicists for the cause of ‘democracy’ was Thomas Paine (1737 – 1809) an Englishman who is credited as one of the Fathers of the American Revolution. Paine arrived in America in 1775 and the next year published his 50 page pamphlet Common Sense (1776). This argued that hereditary monarchy is evil and America should not just revolt against taxation but instead should demand independence. When the French Revolution started Paine published The Rights of Man (1791, 1792) in its defence. In this work he puts forward his formula for the government of a nation. There must be a constitution framed by an elected committee, which specifies the rules and regulations whereby laws are passed and which specify the laws which the government itself must obey. This includes the rules of how the parliament or congress is to be constituted: by election of representatives from roughly equally populated constituencies. In Paine’s scheme there is only one house of parliament because that house is composed of representatives and there is no reason to have a second house of representatives. The house operates within the constitution which is more the guarantee of its wisdom than a second house. Paine omitted to specify how violations of the constitution would be policed.

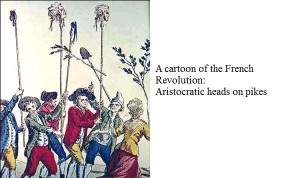

In 1792 Paine was given French citizenship and elected to the National Convention of France given the job of drafting the French Constitution of 1793. By April 1793 he had despaired of the revolution ever bringing liberty as it was rapidly descending into factions and chaos.[8] Paine was jailed and scheduled to be guillotined during the Reign of Terror (September 1793 –July 1794) but survived through un coup de chance. The guillotine claimed over 16,000 in that period. If ever the road to hell was paved by good intentions it was then.

France is now a democracy but its gestation was traumatic. After the Reign of Terror a corrupt government was overthrown by Napoleon (1799) who declared himself Emperor and initiated a series of expeditionary wars finally ending in ignominious defeat in 1815. The monarchy was restored twice followed by two revolutions and a second empire. The stable ‘3rd Republic’ was not established until 1870.

Democracy

These days the establishment of ‘democracy’ is seen as the solution to the problem of troubled and oppressed states. The experience of Iraq and Afghanistan should have abused us of the idea that this as an immediate solution. Voting for a parliament or a president guarantees very little. The separation of powers and the institutions in the country which administer the laws etc must be in place. Democracies depend on a shared national identity– a WE that all (or at least a sizeable majority) respect and recognise. There must be a general recognition of the constitutional limits of the various institutions otherwise ‘democracy’ becomes ‘shoutocracy’ where they who shout the loudest make the rules. ‘Democracy’ becomes a means of imposing one’s will on others.[9] Demagogues bribe sections of the electorate into voting for them (witness the 2015 election campaigns in the UK). The various factions bring the whole process into chaos. Eventually, the populace will prefer a strong leader, such as a Napoleon or a Hitler, who forcefully, even viciously, maintains order.

Philosophy of Mind

The trials and tribulations of living obviously depend to a great degree on the kind of society one is born into and grows up in. This may appear obvious, but it is a view marginalised in current ‘neuroscience’ which views a man as a robot programmed by his genes where his behaviour is determined by electro-chemical activity in the brain. The obvious answer for personal happiness, for criminality, for ‘good citizenship’ is then an appropriate drug which changes the chemical balance in the brain. All Thomas Paine really needed in his prison cell was a good dose of Prozac.

This kind of philosophy of mind requires a rethink. It has led to an epidemic of ‘mental illnesses’ to be treated with ever more forms of medication.[10] To be fair, current neuroscience recognises that the brain changes in response to environmental influences such as education, parental love, economic circumstance, sexual abuse and so on. This is known as ‘neuroplasticity’. The error is that there is nothing in between the environment and the brain. The individual does not as himself do anything and is not responsible for anything: “All those things that you do when you feel that you are using your mind (perceiving, thinking, feeling, choosing, and so on) are entirely the result of the physical actions of the myriad cells that make up your brain.” [11]

Until the ‘mental sciences’ recognise that people have the ability to perceive, understand, imagine, communicate, choose and act, they will flounder around creating as much mental unease as they solve with medication. These abilities are vital to the progress of science and the preservation of democracy, so to deny them is self defeating (literally).

You can read more about this philosophical approach to a science of mind by placing your e-mail address in the green banner at the side of this page.

References

[1] More T (1516) Of a Republic’s best State and of the new Island Utopia available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/2130/2130-h/2130-h.htm

[2] The Centre for Thomas More Studies at http://thomasmorestudies.org/g-c1.html

[3] Plato (ca 380BC) The Republic translation by B Jowett available at http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.html

[4] Hobbes T (1651) Leviathan chapter 13 in S M Cahn (ed) (1977) available at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3207

[5] Locke J (1689-90) Two Treatises of Government available at http://lonang.com/library/reference/locke-two-treatises-government/

[6] Montesquieu C (1748) De l’Esprit des Lois (The Spirit of the Laws) available at https://archive.org/details/spiritoflaws01montuoft

[7] The Leveson Inquiry official website www.levesoninquiry.org.uk

[8] Paine T (1793) letter to Thomas Jefferson 20 April 1793

[9] Billner A & Carlstrom C (2015) Sweden’s Ostracism of ‘Neo-Fascists’ Tests Democracy’s Edge available at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-01-11/sweden-s-ostracism-of-neo-fascists-tests-democracy-s-gray-zone

[10] Scull A (2015) Mad Science: The Treatment of Mental Illness Fails to Progress [Excerpt] available at http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mad-science-the-treatment-of-mental-illness-fails-to-progress-excerpt/?WT.mc_id=SA_WR_20150422

[11] Blakemore C (1988) The Mind Machine BBC Books p7

[amazon_link asins=’B007JYFHVM,B007KNSB24,B008VTB6TQ,B01F9QU1CQ’ template=’ProductCarousel1′ store=’retthemin-21′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’982d4338-4551-11e7-9639-873bb5982f8c’]

Thank you for this remarkable and succinct introduction (or reminder) of the history of democracy. Its subtleties and complexity are welcome in these times of political illiteracy and the consequences of over simplification or incomprehension of different human cultures. Your work triggered some reflections I summarize below.

If one wonders nowadays about the personality one should have to become a successful politician, the result could unfortunately be very far from what is actually chosen by the citizen who elects our governments.

A successful politician should be at ease with Science and Technology since they powerfully contributed to the evolution of the world and our societies since four centuries. The current paradigm of Physicalism is notably an important consequence of their overwhelming success since philosophers created Science. A politician has to be acquainted with both the philosophy which is behind Science and its effects on the material world and the mind.

But we aren’t simple machines and humankind must be deeply and empathically understood by politicians if they are to be successful and able to rally citizens around their leadership. These qualities are best found in artists at ease with humanities than in technicians. Therefore a politician should be at ease with a humanistic way of understanding nature and humankind. This quality could be in contradiction with the scientific quality a politician should have also! The only way to blend these seemingly contradictory qualities seems to be philosophy!

We can conclude that a good politician should be at once at ease with science, art, history and psychology and be a philosopher! Is this really what our political system proposes today to our votes?

Thanks for your interesting comment. To anwer your question: I think not!